Many companion robots are developed for the elderly’s home care purpose, but the elderly often refused to keep themselves company by robots. In collaboration with post-doc researcher Sung-en Chien, I partnered with ASUS to conduct a behavioral experiment on their social robot, Zenbo, with the aim of improving the elderly’s acceptance of companion robots. I designed and implemented a between-subject experiment with 90 participants. By watching other people interact with robots, older adults are able to learn and internalize this positive attitude. The research delved significantly into methods to enhance older people’s acceptance of robots and was published in the 22nd International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (CHI).

Problem

- Isolation can cause a rapid decline in cognitive function for the elderly. In an aging society, using robots to keep the elderly company has become a future trend, and ASUS is one of them. They launched a companion robot, Zenbo, but it turns out the market response is not good because the elderly don’t like robots in general. ASUS want to understand how to increase the elderly’s acceptence toward robots.

- Our prior research found out that letting older adults interact with robots can significantly increase their positive attitude. However, it is impossible to get every older adult interact with robots to increase their acceptence.

- We want to seek possible alternative options, other than direct interaction, to enhance older adults’ acceptance toward robots.

Research Question

If we can learn new things by observing, can we also learn positive attitudes by observing? More specifically, can we let the elderly “observe” other people happily interacting with robots and “learn” this positive attitude?

Methods

-

I Observe; Therefore I Learn

Observational learning is how people learn new things by merely observing, without being taught explicitly. “Example is better than precept” is an depict of how children are good at learning new things through modeling and without being taught by words.

-

Participants

- We recruited 80 participants, including 40 younger adults and 40 older adults

- 4 groups in total. Each group has 20 people (2 x 2 between-subject design)

- young adults x older adults

- control x treatment (observational learning)

-

Intervention

Each Participant watched a 3 minutes long video- The treatment groups watch a video in which a person is interacting with Zenbo

- The control groups, in contrast, watch a video in which no people presents, but only Zenbo is introducing itself

-

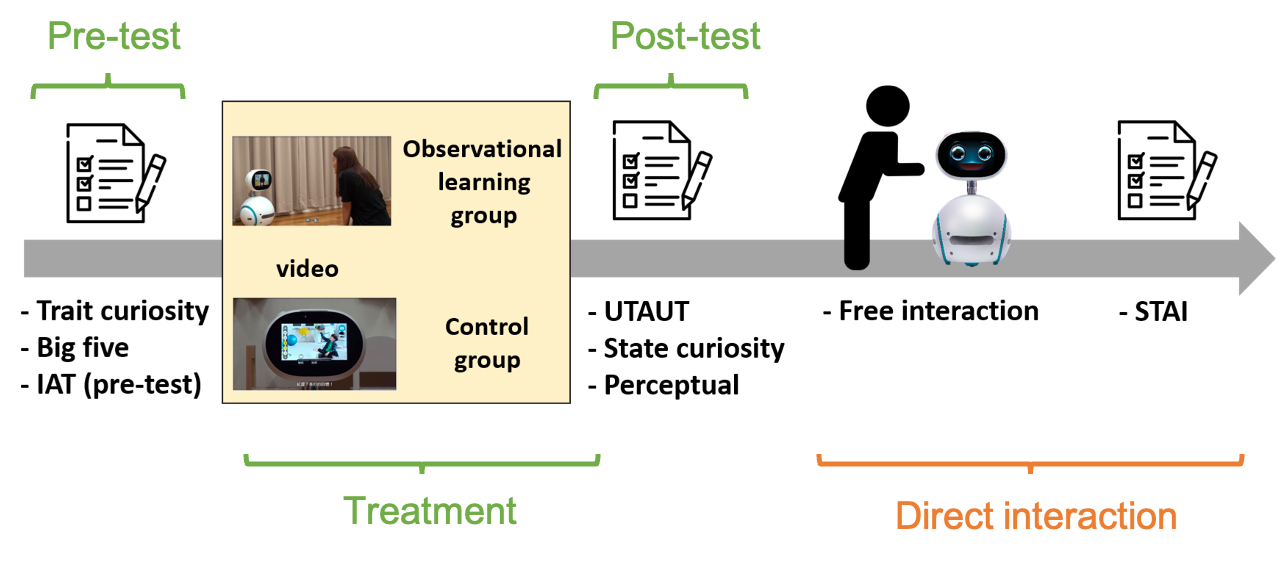

Experiment Procedures

I seperated the experiment into two phases:- Observational learning phase (green): A pre-post test design. Here I applied observational learning and measured its effect on attitudes.

- Direct interaction phase (orange): Here I observed how observational learning could impact our participants' real-world behavior with robots.

-

Measures

I used several questionnaires and computerized cognitive testing for measuring implicit attitudes, explicit attitudes, and personality.- Questionnaire

- Trait curiosity questionnaire

- Big Five Personality Test

- Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

- State curiosity questionnaire

- Subjective Technology Adaptivity Inventory (STAI)

- Computerized cognitive testing

- Implicit association task (IAT)

- perceptual matching task

- Questionnaire

Two Main Findings

1. Hey Zenbo, do you love me?

The elderly do seek emotional supports from robots.

2. Observational works!

The elderly can “observe” other people happily using robots and “learn” this positive attitude.

More Detailed Findings

-

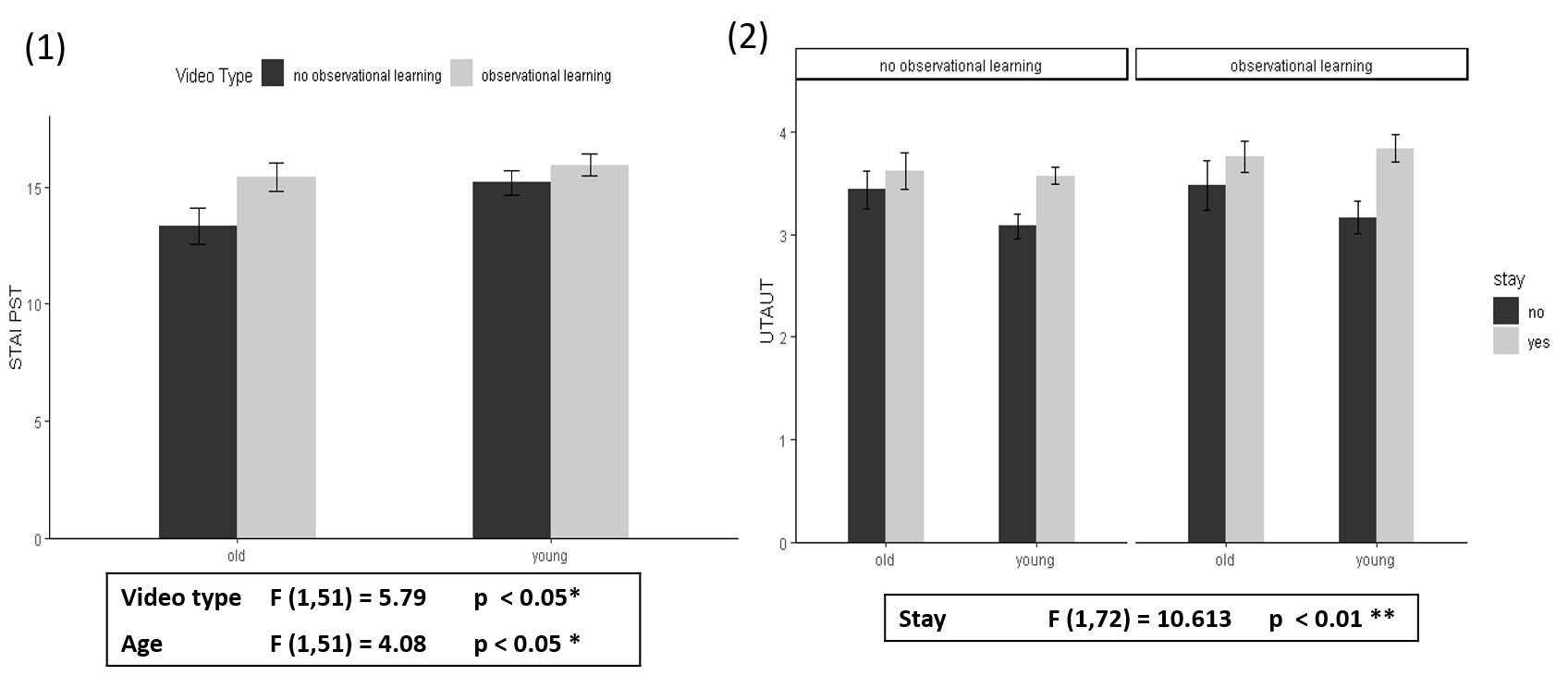

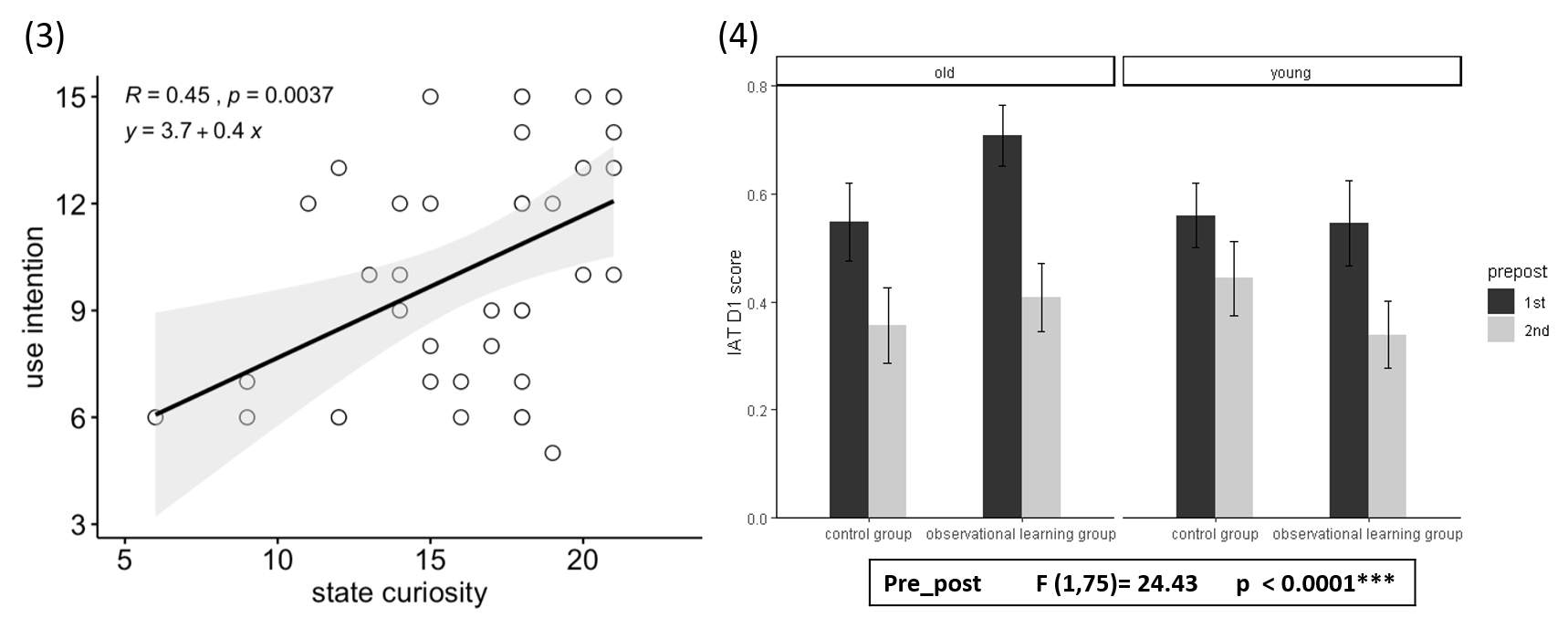

The effect of observational learning appeared after direct interaction with Zenbo. The observational groups show higher scores in perceived safety of technology (PST) in STAI.

-

In general, participants with higher UTAUT score, which indicates a higher self-report acceptence, were more willing to stay and to interact with the robot.

-

In the observational learning group, participants with a higher state curiosity also had a higher use intention toward the robot.

-

Regardless of age and video type, the D1 score of IAT declined after watching the video. The result implied that the implicit attitude toward robots could be changed in a short period of time (A high D1 score means a higher negative attitude).

Reflections

-

The necessity of direct interaction

The results shows that the effect of observational learning appeared after direct interaction with Zenbo, inferring that direct interaction still has its necessity. Despite that, we still find that observational learning has some impact on the acceptance of robots. -

Reduce the number of measures

Too many measures in one research might lead to fatigue. For example, to measure implicit attitudes, we may not need to include both the perceptual matching task and the implicit attitude task. -

Using a senior as the character in the treatment video instead

The observational learning video is a video in which a young adult interacts with the robot. Using an older adult as the character might have a different impact on our senior participants and thus bring us different results. -

The plunge in the IAT D1 score in 2nd round need further research

The meaning behind the plunge of the IAT D1 score in the 2nd round requires further research to investigate, especially when the plunge is more obviously observed in the older adult participants. We are yet not sure if it is a practice effect or a decline in implicit attitudes.

References

-

Yi, M. Y., & Davis, F. D. 2003. Developing and validating an observational learning model of computer software training and skill acquisition. Information Systems Research. 14(2), 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.2.146.16016

-

Sung-En Chien, Li Chu, Hsing-Hao Lee, Chien-Chun Yang, Fo-Hui Lin, Pei-Ling Yang, Te-Mei Wang, andSu-Ling Yeh. 2019. Age Difference in Perceived Ease of Use, Curiosity, and Implicit Negative Attitude towardRobots. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot Interact. 8, 2, Article 9 (May 2019), 19 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3311788

-

Chu, L., Chen, H. W., Cheng, P. Y., Ho, P., Weng, I. T., Yang, P. L., … & Fung, H. H. 2019. Identifying Features that Enhance Older Adults’ Acceptance of Robots: A Mixed Methods Study. Gerontology. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494881

-

Lhuisset, L., & Margnes, E. 2015. The influence of live-vs. video-model presentation on the early acquisition of a new complex coordination. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. 20(5), 490-502. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.923989

-

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. 1961. Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 63(3), 575-582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0045925

-

Heerink, M., Kröse, B., Wielinga, B., & Evers, V. 2008. Enjoyment intention to use and actual use of a conversational robot by elderly people. Proceedings of the 3rd ACM/IEEE international conference on Human robot interaction. 113-120 https://doi.org/10.1145/1349822.1349838

-

Hassani, A. Z. (2011). Touch versus in-air Hand Gestures: Evaluating the acceptance by seniors of Human-Robot Interaction using Microsoft Kinect .Master’s thesis. University of Twente, Netherland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25167-2_42